In February 2013, the first human infections with influenza subtype H7N9 were observed in coastal China. As our group is currently in the process of processing samples from a large serosurvey in southern Vietnam, we analyzed our data to determine if antibody levels in the Vietnamese population to H7 influenza subtypes were higher or lower than expected. One key reason to look at this was recent interest in whether raised human antibody levels to avian influenza viruses actually corresponded to evidence of past infection or a degree of immune protection.

We analyzed data on 1723 general population serum samples from Ho Chi Minh City and Khanh Hoa province (300km to the northeast of Ho Chi Minh City) which were assayed by a protein microarray method for antibodies to influenza subtypes H1, H3, H5, H7, and H9. Antibody titiers are summarized by age and subtype in the graph below.

Three different H5 strains were used in the assays, and one strain each of H7 and H9. The three red lines in each mini-scatter in the plot above correspond to the 70th, 80th, and 90th percentiles of the data, showing that the majority of individuals had titers lower than 40. It’s clear that antibody titers are highest for H9 and lowest for H5. And it’s also clear that antibody titers increase with age. But, we don’t know whether a high titer — as measured by a newly developed protein microarray — corresponds to past infection or protection.

Our suspicion — based on the facts that high titers were seen for H5 viruses and that all antibody measurements increased with age — was that the high titers were not the results of past infections with H7N9 or another avian influenza virus. Given previous interpretations of avian influenza antibody titers in humans, our best guess was that the high avian titers were cross-reactions, in the assay, generated by high concentrations of antibodies to H1 or H3 influenza viruses (the subtypes that circulate in humans). When we inspected individuals with high titers to H7 or H9, we found that they also had very titers to H1, H3, or both.

We felt that we could exploit the difference in locations, one urban and one periurban with patients coming from rural areas, to determine if there was any evidence of true exposure to avian influenza viruses. Only 5.4% of households in Ho Chi Minh City own domestic chickens or ducks, but in Khanh Hoa province this figure is 38%.

We regressed log avian influenza titers (T) onto age and onto the geometric mean antibody titers (GMT) across the human influenza antigens.

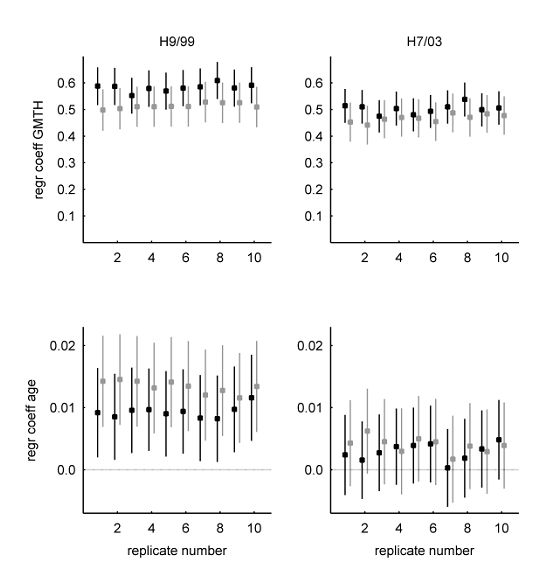

In order to do this correctly, we had to subsample the two sites to make sure that their age distributions matched exactly. The plots below show the regression coefficient β1 (top row) and β2 (bottom row) for ten subsampled replicates of the data. HCMC estimates are shown in black, and Khanh Hoa in gray.

For H7, the 95% confidence intervals of the regression coefficients in the two locations have a lot of overlap. When comparing HCMC and Khanh Hoa, it appears that age and human influenza antibody titer have similar effects on the measured H7 antibody titer. Had we seen different effects, we could have hypothesized that human influenza exposure is lower in Khanh Hoa than in HCMC, and that avian influenza exposure is higher in Khanh Hoa than in HCMC.

For H9, the story looks similar. But the differences in the bottom left panel leave us wondering what would be seen with larger sample sizes.

Click here for the published article in Journal of Infectious Diseases.